Making sense of our story

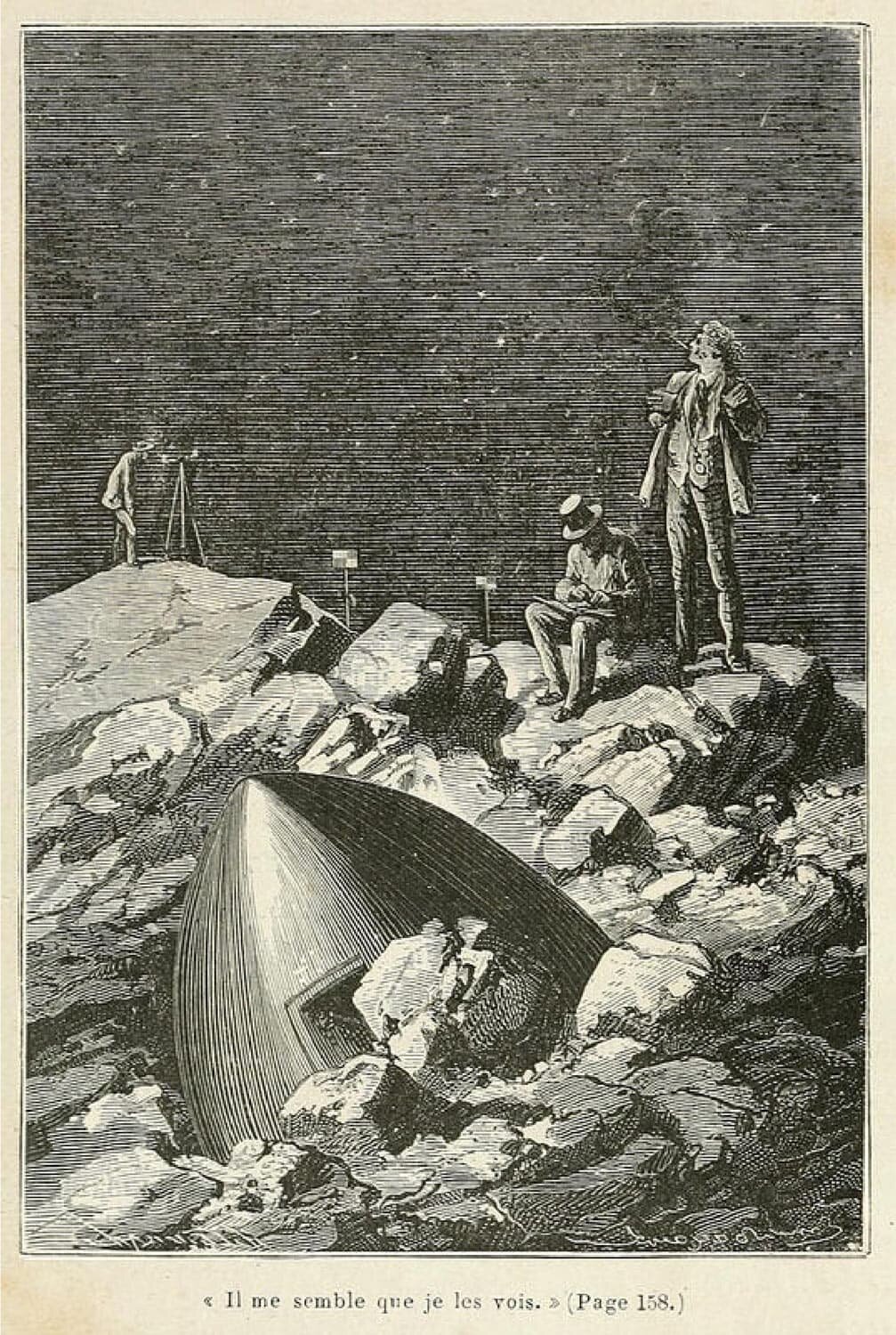

Joseph Campbell’s map of the Hero’s Journey, in black, is illustrated by eight color-coded stories that help us see ourselves within the eternal pattern.

Myths are stories that help us make sense of our lives. They map the human journey, guide us towards our potential, connect us to the Eternal, and reveal the pattern of a well-lived life.

The pattern, most simply, is a circle. We leave and we return, changed. Myth is a story of transformation, a call to step forward, to grow and expand, to return and enrich the world. Myth is the path connecting who we think we are with who we really are.

Like Dorothy Gale of Kansas, what black and white world am I stuck in? Like Siddhartha, what palace must I leave? Like Harry Potter, what greater role beckons me? Who, like Obi Wan, is calling me to a greater adventure? Like Sir Gawain or Frodo Baggins, what courageous act am I capable of, despite my fears?

Like Jesus, how am I called to question and oppose the established thinking that surrounds me? Like Anakin Skywalker, how do I bring the light and dark forces of my life into balance? Like Pinocchio, in what ways am I foolish and wooden, and how can I become more fully human?

The first story I remember was from when I was about two or three. My mother would read it to me over and over again. It was the story of a clever South Indian boy who tricked a series of ferocious tigers into chasing each other around and around a pole until they turned into butter, which the boy’s mother used to make delicious pancakes.

I couldn’t get enough of this story, and I am not sure why. I believe the attraction was how this clever little boy could breezily face down mortal danger using only his humor and wits.

The next story that made a big impression was David and Goliath. Similar theme: a vulnerable boy outmatched by a merciless enemy, whom he defeats without muscle or armor, only a rock and sling, and irrational courage in the face of hopeless odds.

But the first story to really do a number on me, get into my bones, fascinate and perplex me, was about a young boy living in the American Old West who forged a bond with a rascally and independent dog.

Rabies was spreading, infecting animals with the threat that they could attack and kill human beings. I remember the image of the family cow foaming at the mouth, stumbling. I didn’t really understand what rabies was, but I was terrified by it. When a wolf approaches the boy’s family, the dog risks his life to fight it off. And with the dog now at risk for rabies, the family locks him in a shed to see if he develops the disease.

When they crack open the shed door to check on him, the dog bursts out, foaming at the mouth and snarling, and the boy has to make the terrible decision to grab the family shotgun and kill him.

Old Yeller. Devastating.

It is only when the boy sees one of Old Yeller’s offspring behaving in a way that reminds him of his old friend that he finally agrees to accept the puppy as his own.

What is it with that story? Why did I keep coming back to it? It’s such a sad story, but not just sad, complex. An animal that you initially reject becomes your most loyal friend, willing to give its life to save you, but then you have to take its life? And then the cycle starts again, with all the same potential for transcendence and tragedy. It held a complexity that reflected the bewilderment I experienced as a small boy, where random frightening events sometimes happen, where loved ones can turn dark, where one day your best friend may unaccountably sucker punch you in the gut, leaving you gasping for air on the ground—and where beauty and miracles somehow always manage to be inexplicably, unexpectedly present.

Stories are tools for helping us see life’s patterns. Stories help us make sense of our lives.

We drop into this strange life like magically appearing in a carnival, filled with every imaginable experience. What’s going on here? Who am I? Who can I trust? What is safe, and what is dangerous? How am I to work my way through this journey? What are the patterns to pay attention to here?

We are pattern-seeking creatures. We take in everything around us, and organize it into categories that help us understand and navigate our world. Stories are tools for helping us see life’s patterns. Stories help us make sense of our lives.

The basic form of a story is: A character wants something, and then something happens. We find this interesting because it helps us understand our own experience of being in the world—wanting something, moving towards it, having something outside of our control disrupt our plans, choosing how we respond, and being changed by the experience. Stories mirror our personal experience of being alive in a way that comforts and reassures us, informs and guides us.

Stories help us answer: What is worth wanting? What is worth reaching towards? What are appropriate ways of attaining what we want? What is the role of others in helping or hindering us? How do we deal with the fear of not getting what we want, or the consequences of getting it? How do we respond to hardships or barriers to our plans?

What wants to live in the world through me?

1. Stuck

Myths dramatize themes we find ourselves frequently encountering in our lives. The story often begins in a place of discomfort, or maybe too much comfort. Where do we experience stuckness in our lives? When are we constricted by a situation that feels limiting and confining, that holds us back and diminishes us?

2. Called

The call to adventure can be a whisper or a lightning bolt. It’s sometimes dramatized by the troll who beckons us to cross a bridge. The call frequently ‘doesn’t make sense,’ but resonates deeply. Listening for the call can activate and magnify it. When we pay attention and quietly listen, what do we see and hear calling us forward?

3. Trials

Saying “yes” to the call can be exhilarating, and then we’re hit with reality: oceans to be crossed, forests to find our way through, dragons to be slain, wolves and bears and stormtroopers to be confronted. These trials aren’t just bumps in the road, but feel terrifying, hopeless, impossible.

4. Helpers

We must take responsibility for our own journey, but we are never alone. Who are the people who show up in our lives to give us courage and assistance when we most need it? When do we play that role for others on the journey?

5. Transformation

We say yes to a path that leads to a larger version of ourselves. We let go of one life and reach towards another, and face the consequences of our choices, from devastation to liberation. Regardless, we are irrevocably changed.

6. Return

The journey isn’t complete until we return to share the gift we have received. We feel and acknowledge our deep connection to life’s unseen forces. We receive blessings and are expanded, and feel moved to live and express our unique gift in service and gratitude—and start the journey again.

The shared stories we tell create the value systems that shape and define us and bind us in community with others. The stories told within families, social and religious groups, cultures, and countries define who they are, what they believe, and how we are to behave as a member of that group. All of our individual daily choices are informed by whatever stories are ingrained in us, consciously or not. Our stories are our operating systems.

Joseph Campbell identified and organized a certain type of story told across cultures around the world and throughout time. He called this story the Hero’s Journey, and he wrote about it in his 1949 book, The Hero With a Thousand Faces.

There are values and morals contained in these hero stories—how to behave in a society and so forth—but the reason that they continue to resonate within us and grip us over time and culture is their ability to capture and convey the mystifying and often paradoxical qualities of living a meaningful and satisfying human life.

Is there a thread to follow in Campbell’s map that will lead us forward, see us through the chaos, give our lives meaning, connect us to ourselves, each other, the planet, and unseen forces? I believe so, but it is hard to pin down. Even with Campbell’s precise and powerful language, achieving or attaining “apotheosis” seems to be beyond instruction or a purely intellectual understanding.

So we read the stories, and let them work on us.

We all have gifts to be lived. There is a magnified version of each of us that wants to be expressed—and in its full expression, we enrich the world.

Last year, driven by my own search for understanding, and the desire to touch people the way I have been touched by the power of story and Campbell’s interpretation and translation of it, I created a letterpressed print of the chart created by Campbell, illustrating his pattern of the journey with color-coded narratives from eight classic stories, from Luke Skywalker to Siddhartha, Jesus of Nazareth to Dorothy of Kansas, Harry Potter to Sir Gawain. I made 500 of these prints and sent them to people whose work I admired, people who have inspired me, people I love.

We all have gifts to be lived. There is a magnified version of each of us that wants to be expressed—and in its full expression, we enrich the world. This gift can only be discovered by a complete surrender to discovering and living the personal and peculiar story that calls to each of us, at the expense of anything that stands in its way—any story foisted upon us by others, any story that is too small or that we have outgrown.

That’s the most powerful insight that I take from Campbell: that our transformation is in our own hands, and it doesn’t begin in defeating dragons or Death Stars, but in intentionally choosing what story we believe most worth telling and living in our own life, and in the shared pursuit of a story large enough to include us all.

Originally published in Watkins Mind Body Spirit Magazine